Illustration 1: Live set by T3 and Step.jad recorded for the Chengdu Community Radio, April 23, 2020.

Thursday, April 23rd. It has already been dark for a couple of hours here in Vancouver, Canada, when I connect to the Internet to follow a live show from Chengdu. In China it’s 3pm and the Chengdu Community Radio invited two local artists, T3 and Step.jad, to play a livestreamed set broadcast from their Bilibili channel. With the Covid-19 pandemic expanding worldwide in the first semester of 2020, livestreaming has become a common practice for a lot of musicians that have been stuck at home too. In the scientific literature, livestreaming is being defined as ‘a broadcast video streaming service provided by web-based platoforms and mobile applications that feature synchronous and cross-modal (video, text, and image) interactivity.’This practice is not new in the music industry but the cancellations of live performances and the massive economic loss caused by the shutdown of stages have led to an inevitable shift from offline music live shows to online music livestream. At a time where more and more countries are easing physical restrictions in the fight over Covid-19, it seems interesting to adopt a general overlook on this modern practice and to ask ourselves: is livestreaming the post-Covid-19 future for live music?

Illustration 2: One of the first livestreamed concert by the Rolling Stones (1994).

Livestreaming: a life before Covid-19

Music livestreaming is not a new window that just opened with the Covid-19 pandemic. Thanks to technological development, it is said that the Rolling Stones were the first major band to embrace the trend by livestreaming their show in Dallas, 1994. At that time, professionals in music already acknowledged the important role the internet could play in music promotion. This assessment hasn’t changed through the years but new platforms have emerged: YouTube live and Twitch appeared in 2011, Facebook live in 2015, Instagram live in 2016. With the world’s largest livestreaming industry (504 million users in 2019), China has developed its own platforms such as Bilibili (B站), Kuaishou (快手) and Douyin (抖音). Before the Covid-19 outbreak and the worldwide shutdown of live venues, those platforms were already used by musicians and music venues as a way to promote music and to connect with a wider audience. Livestreaming actually didn’t intend to replace live shows but offer another string of revenue by enlarging fan engagement and online reach. One successful illustration of this use is the 2019 edition of the festival Coachella that gathered more than 82 millions views online while it only welcomed 250,000 people on site.

Illustration 3: The Wiltern Theatre, Las Vegas, 2020.

Venues shut down and economic loss

In the first semester of 2020, music industry has been impacted worldwide. In late January, the Chinese live venues closed and music festivals were either postponed or cancelled. In Europe and in the USA, following a slow decrease in authorisations of gatherings, public venues were shut down and events cancelled around mid-March. On its website, Billboard tries to list all the major music events that have been cancelled due to Covid-19. Whether independent artists, underground venues, major arenas, mainstream rock stars or big labels, everyone has been economically impacted by this unprecedented sanitary ban on live performances. In the first trimester, 20,000 concerts have been cancelled in China generating a loss of $286million. In the United States, the live music business was supposed to generate $12.2 billion in 2020 but these expectations might be amputated by almost $9 billion. The economic outburst impacts beyond the artists themselves: security agents, merchandising sellers, crew members, roadies, independent contractors are all facing unemployment without necessarily being able to get any other revenue. The cancellations of music festivals also had a wider range of consequences and endangered local economic actors that benefited from their attraction on the area.

Illustration 4: Travis Scott’s concert on Fortnite, April 23-25, 2020.

A worldwide move to livestream platforms

With live music forced to stop overnight, artists and venues massively turned to livestream platforms to keep engaging with their audiences. First artists to be stuck at home, Chinese musicians were naturally the first to propose quarantine livestreaming. The Strawberry Z festival gathered seventy bands over five days on Bilibili, Taihe Music organized the I’m fine云趴音乐周 bringing twelve hours of music everyday on Kuaishou. Cloud disco (云蹦迪) also invaded the Chinese livestreaming platforms with famous clubs like TAXX or One Third inviting their customers to move the party online. With the virus expanding over the world, the same pattern could be observed abroad. Musicians in Europe and in America took over the Internet to propose home-concerts on live platforms like Facebook or Youtube. Websites like Bandsintwon, Shotgun and Resident Advisor gather information about all the live streaming concerts happening during the pandemic and the number of shows is gigantic: on March 25th, Bandsintown gathered information about more than 8,102 live stream events. If the majority of the artists mapped here are medium or small-scale artists (the most impacted by the impossibility to play on stage), big celebrities also tuned in like Travis Scott who gave a historic show on the videogame Fortnite, gathering over 27 million players.

Illustration 5: Music for Hope, livestream of Andrea Bocelli in the Duomo, Milano, April 12, 2020.

Like a bridge over troubled water

In uncertain times, listening to music plays an important psychological role in people’s life. As David Hesmondhalgh reminds us in Why music matters ?, music is a very intense and emotional experience linked to the personal self. In this time where live venues around the world have been shut down and emotions cannot be expressed on stage nor in the audience, online platforms open a space where artists and music lovers can meet and support each others. In her article on the livestreaming of the Seattle Symphony, Brooke Jarvis testifies how the beauty of such a moment helped her to cope with a mental breakdown: I almost cried. The livestreaming experience, might also provide the very rare opportunity to share an intimate experience with artists stuck at home or in the comfortable environment of a recording studio. In China, cloud disco has been a window for the Chinese youth stuck for months inside their apartments. In Wuhan or in New York City, it has been yet another opportunity for people to dance, sing and release pressure from the disasters happening outside.

Illustration 6: An illustration of the Bilibili interactive reactions during a Strawberry Z concert.

To recreate the social experience

With more than half of the world population forced to stay at home, livestreaming platforms also participated in bridging the social gap by providing a common and immersive experience into music. Music [...] represents a remarkable meeting point of intimate and social realms.. Online, people all over the planet can instantly gather and enjoy live shows. Music fans from remote areas have access to cultural content they usually can’t enjoy. In the past months in Vancouver and without leaving my sofa, I’ve been attending concerts from Chengdu (China), New Brunswick (Canada), Los Angeles (USA) and Britanny (France). Livestreaming also redefines the codes of the live experience. In his ethnographic observation of Kadavar livestreamed concert on Facebook live, Gérôme Guibert notes some similarities with a normal gig but also new features that only exist in this format: the concert is happening in a living room, there is no light system and everyone can see every detail of the set. A second screen with a live chat allows people in the audience to share messages with each other and cope with their social isolation. Brooke Jarvis also noted how the livestreamed format enhances interaction among the classic music audience who enjoy sending clapping emojis in the middle of an act while social norms would forbid such a behavior in a real life performance. In terms of interactivity, the Chinese platform Bilibili is actually standing out by providing the most integrated feature for audience to react in real-time thanks to bullet-comments (弹幕) superimposed over the video. This kind of visual commentary track makes the events an active expression of community and social bonding, rather than just passive experiences.

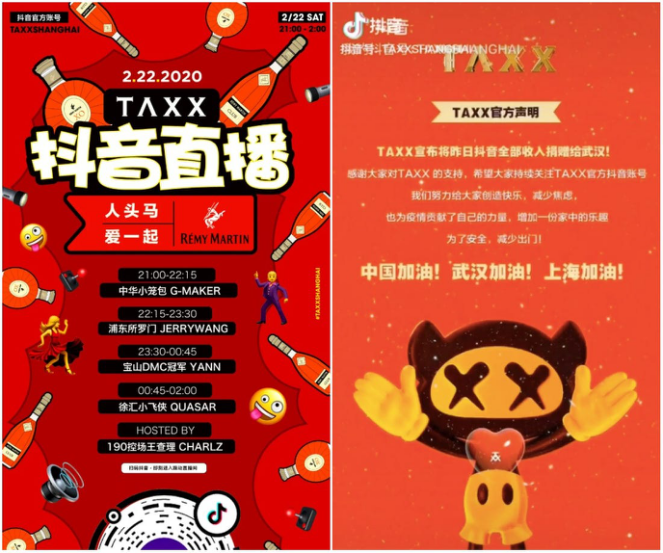

Illustration 7: During a livestream party on Douyin, TAXX raised more than RMB700.000

A new stream of revenue for the music ...

Livestreaming concerts was providing another string of revenue for music professionals before the Covid-19 outbreak but for some now it might represent the only string left. In China, where artists’ economic model relies heavily on live performances, it has been a perfect time for creation but a lot of musicians made no money. Digital platforms enabled them to keep on working while opening a new monetary stream: audience can tip the artists, make donations and even buy merchandising online. Live venues also tuned in to let their usual customers benefit from live concerts. As a venue, our advantage is what we currently have: the venue space, the equipment, and our tech crew. Some clubs have found a lucrative space to raise money: the two Chinese clubs TAXX and One Third respectively raised RMB 700,000 and RMB 1million during cloud disco parties on Douyin. This money represents a temporary fix for music venues that can finally cash in and even pay some of their staff. But it should be noticed that even if venues and musicians are severely hit by the pandemic, they often connect online performances to charities and spur their fan base to donate for hospitals, front line workers and associations linked to the pandemic.

Illustration 8: LiveXLive is an American livestreaming platform working with several musicians.

… but an uncertain economic development

While live venues remain closed in most of the countries, some limits of livestreamed events also force us to relativise its role in the post-Covid-19 era. Economically, livestreaming is far away from having covered up the losses of the earthquake experienced by the living spectacle in the past months. If some famous Chinese clubs managed to earn good money on a couple of dates, cloud disco remains a promotion tool to incite clubbers to come back to the physical place once reopening allowed. For festivals and live venues, the actual livestreaming format is not as lucrative as offline events with tickets and beverages sales. The main concern for livestreaming lies in its ability to monetize such shows. Monetization can take different forms: advertisement, tips, paid entrance, subscription to a closed platform, etc. So far, it is hard to say if people will be ready to pay to access such contenteven if a study by Bandsintown reveals that more than 70 % of music fans on the platform are willing to pay to support streaming artists. Nevertheless the systematization of online shows also raises the question of authorship, recording and reproduction rights and still represents a big puzzle that has to be answered accordingly to the different platforms and national legal systems.

Illustration 9: How to behave behind a screen ?

Audience behaviour and standardization of performance

Another concern with the future of livestreaming lies in the core of this practice itself: the performance. As Gérôme Guibert reminds us, playing in an empty venue might be suitable for some music styles but not for popular music where the bodies are meaningful, maybe crucial and where the show is also in the venue itself. The feelings of bodies, the dancing, the mixture of smells of the venues and the alcohol, the sight and the hearing altered by the lights and the sound system: those characteristics are hard or impossible to reproduce through a screen. The destruction of the unity of time and place forces the audience to readjust its behavior, from being part of a collective musical rite to a passive and potentially solitary reception. How does the livestreaming audience behave? Shall we dance or stay seated, shall we drink, sing and yell or should we adopt a peaceful watching, closer to a cinema experience? Eventually, livestreaming might represent a threat to the creation itself. Every live show is different and musicians are constantlyrenewing themselves in order to entertain the audience. With only a few platforms available and an increasing number of bands rushing to give livestream concerts all over the world, it is to be feared that the uniqueness of live music would be turned into a senseless mechanical reproduction. The standardization and commodification of a magical, rare and ephemeral musical moment, would be detrimental both to the less-famous artists and to the music fans. The promptness of the pandemic postponed these reflections but, like anytime when technologies develop, a reflection on the evolution of its uses will have to be done.

Conclusion

Live music has always been evolving and borrowing from new technologies. I can still remember the shock, when in 2012 Tupac Shakur (assassinated in 1996) appeared on the Coachella stage under the form of a hologram. Livestreaming and the performance of Travis Scott in a video game is only the evolution of such an imbrication of music and technological progress. By forcing people to stay at home and shutting down live venues, the outbreak of Covid-19 didn’t give birth to music livestreaming but reinforced the digitalization of culture and forced its agents to rethink their practice. While a generalization of livestreaming concerts seems not likely to happen when the pandemic will be under control, this tool has shown some very interesting assets that could be merged into the future of live music. Maybe, the greatest contribution this sanitary crisis had is that it finally pointed out the need for a change and forced the music industry to reconsider its center of gravity around live performances. Because for most of us now, the idea of going to a 300-cap venue and pushing through some asshole crowd of kids to pay for an $18 beer, just to stand in a corner and nod my head to some music that is never as good as the record, seems just like hell.

Writer:Grégoire Bienvenu

中文翻译请见 http://icsf.cuc.edu.cn/2020/0908/c5607a172743/page.htm

Referencing List:

Cunningham, S., Craig, D., & Lv, J. (2019). China’s livestreaming industry: platforms, politics, and precarity. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(6), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877919834942

Strauss N. (1994, November 22). Rolling Stones Live on Internet: Both a Big Deal and a Little Deal. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/11/22/arts/rolling-stones-live-on-internet-both-a-big-deal-and-a-little-deal.html

Lee, E., Jiayi, S. (2020, March 9). Brands turn to livestreaming as China stays at home. Technode. https://technode.com/2020/03/09/insights-brands-turn-to-livestreaming-as-china-stays-home/

Kirn, P. (2020, February 11) In quarantined China, concerts and clubs are going online as a safe place to meet. Create Digital Music. https://cdm.link/2020/02/coronavirus-online-music-streaming/

Hu, C. (2020, March 17). How Livestreaming Is Bridging the Gap Between Bands and Fans During the Coronavirus Outbreak. Pitchfork. https://pitchfork.com/thepitch/music-livestreaming-coronavirus/

Hissong, S., Millman, E., Wang, A.X. (2020, April 15). The Week the Music Stopped. Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/music-crisis-concerts-tours-980968/

Zhang, B. (2020, February 2). Coronavirus Paralyzes China's Live Sector as Concert Cancellations and Box Office Losses Mount. Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/international/8551043/coronavirus-paralyzes-china-live-music-sector-concerts

Hissong, S., Millman, E., Wang, A.X. (2020, April 15). The Week the Music Stopped. op.cit.

Desbois, J. (2020, April 16). Le poids économique des festivals bretons. Ouest France. https://www.ouest-france.fr/bretagne/le-poids-economique-des-festivals-bretons-6810235

Feola, J. (2020, February 12). Amidst Coronavirus Lockdown, Musicians in China Livestream the Party. RADII. https://radiichina.com/amidst-coronavirus-lockdown-musicians-in-china-livestream-the-party/

任彤瑶. (2020, February 17). 到底什么是 “云蹦迪” ? (In the end, what is cloud disco?). The Paper. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_6031121

Frankenberg, E. (2020, April 20). Livestream Data Shows Surging Online Activity While Live Venues Remain Closed. Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/chart-beat/9360625/livestream-data-surging-online-activity-venues-closed-coronavirus

Holmes, C. (2020, April 24). I’ve Never Played Fortnite, But Was Forced to Attend Travis Scott’s Fortnite Concert. Rolling Stones. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/travis-scott-fortnite-concert-989209/

Hesmondhalgh, D. (2013). Why music matters ? Wiley-Blackwell.

Jarvis, B. (2020, March 24). Livestreaming the Seattle Symphony Became a Source of Connection in Dark Times. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/24/magazine/coronavirus-music-live-stream-concert.html

Hesmondhalgh, D. (2013). op.cit.

Guibert, G. (2020, April 6). Is livestream real life ? Une soirée concert en confinement. SURVI. https://virus-survi.fr/is-livestream-real-life-une-soiree-concert-en-confinement

Jarvis, B. (2020, March 24). op.cit.

Raghav, K. (2020, February 13). Under Lockdown and Quarantine, China’s Punk Rock Bands Are Taking the Mosh Pit Online. Hyperallergic. https://hyperallergic.com/542468/under-lockdown-and-quarantine-chinas-punk-rock-bands-are-taking-the-mosh-pit-online/

Interview on Wechat with Luna Li, Chengdu local DJ. (2020, March 10).

Feola, J. (2020, February 12). Amidst Coronavirus Lockdown, Musicians in China Livestream the Party. RADII. https://radiichina.com/amidst-coronavirus-lockdown-musicians-in-china-livestream-the-party/

任彤瑶. (2020, February 17). op.cit.

Cici. (2020, February, 20). 2020, 线上演出元年 ? (2020, year of online performance?). The Paper. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_6047433

Thibault, M. (2020, April 28) Le live stream survivra-t-il au déconfinement? IRMA. https://www.irma.asso.fr/Le-live-stream-survivra-t-il-au

Courtney, I. (2020, April 21). Bandsintown Becomes A Hub For Music Live-Streaming. Celebrity access. https://celebrityaccess.com/2020/04/21/bandsintown-becomes-a-hub-for-music-live-streaming/

Hu, C. (2020, April 8) The legal underbelly of livestreaming concerts. Water & Music. https://www.patreon.com/posts/legal-underbelly-35791016

Guibert, G. (2020, March 18). op.cit.

Guibert, G. (2020, May 10). Distanciation physique, communication sociale et musique live. SURVI. https://virus-survi.fr/distanciation-physique-communication-sociale-et-musique-live

Hissong, S., Millman, E., Wang, A.X. (2020, April 15). op.cit.